This post originally appeared on my newsletter, “Open + Worlds.” Subscribe here.

“The meaning of a word is its use in the language.”—Ludwig Wittgenstein

A shorter newsletter this week and a return to the topic of video games. I’ll have more to say on “melodrama” in a future newsletter, especially in relation to video games and the question of morality. Let me know what you thought of last week’s newsletter—feedback will help me to gauge future topics!

A game that I’ve been playing, and enjoying, a lot is Control (2019), which was developed by Remedy Entertainment in Finland. Remedy is best known for their work on a number of action-adventure shooter games, including the Max Payne series (2001, 2003), Alan Wake (2010), and Quantum Break (2016). Like Remedy’s earlier games, Control is an action-adventure game, but it combines elements of shooter, noir, fantasy, and survival horror games. It’s a stylish game, with an intriguing mythology; if you’ve ever dreamt of telekinesis, then this is the game for you. It also has surprisingly challenging mechanics, including a very sensitive life gauge. There were so many moments throughout where I would feel confident in my run, only to die a second later. As a result, I thought the game rewarded experimentation and adaptability—I could never brute force my way to winning a battle; if a previous strategy didn’t work, I’d have to rethink my options and adapt.

It’s also a game that has me thinking about perspective, or point of view. Control utilizes third-person perspective, or over-the-shoulder perspective, so the camera is positioned just above and behind the game’s protagonist Jesse Faden. (In reality, the camera is mobile, not fixed, so it can be repositioned at almost any angle around Jesse. However, during gameplay, the camera will lock above and behind her, giving the player a spectatorial, but immersive, experience.) The conventional argument is that third-person games allow for a more detached, omniscient gameplay experience, whereas first-person games provide greater immersion. (Some games will let you switch between first- and third-person perspective; others will not.) For example, Linda Hutcheon writes that the first-person role “provides a more immediate relationship with the character and a greater immersion in the animated world of the game.”1 This might be overstating it. Unlike in the novel, first-person perspective in video games often entails the elision of character, a flattening out of the character to the mere artifacts of arms and hands. Third-person, meanwhile, allows for greater depth and range of characterization because we do not so much see as the character but see the character seeing the world. Another way of framing the conventional argument might be that first-person prioritizes the inner experience of action, whereas third-person prioritizes the effects of that action in the outer world.2

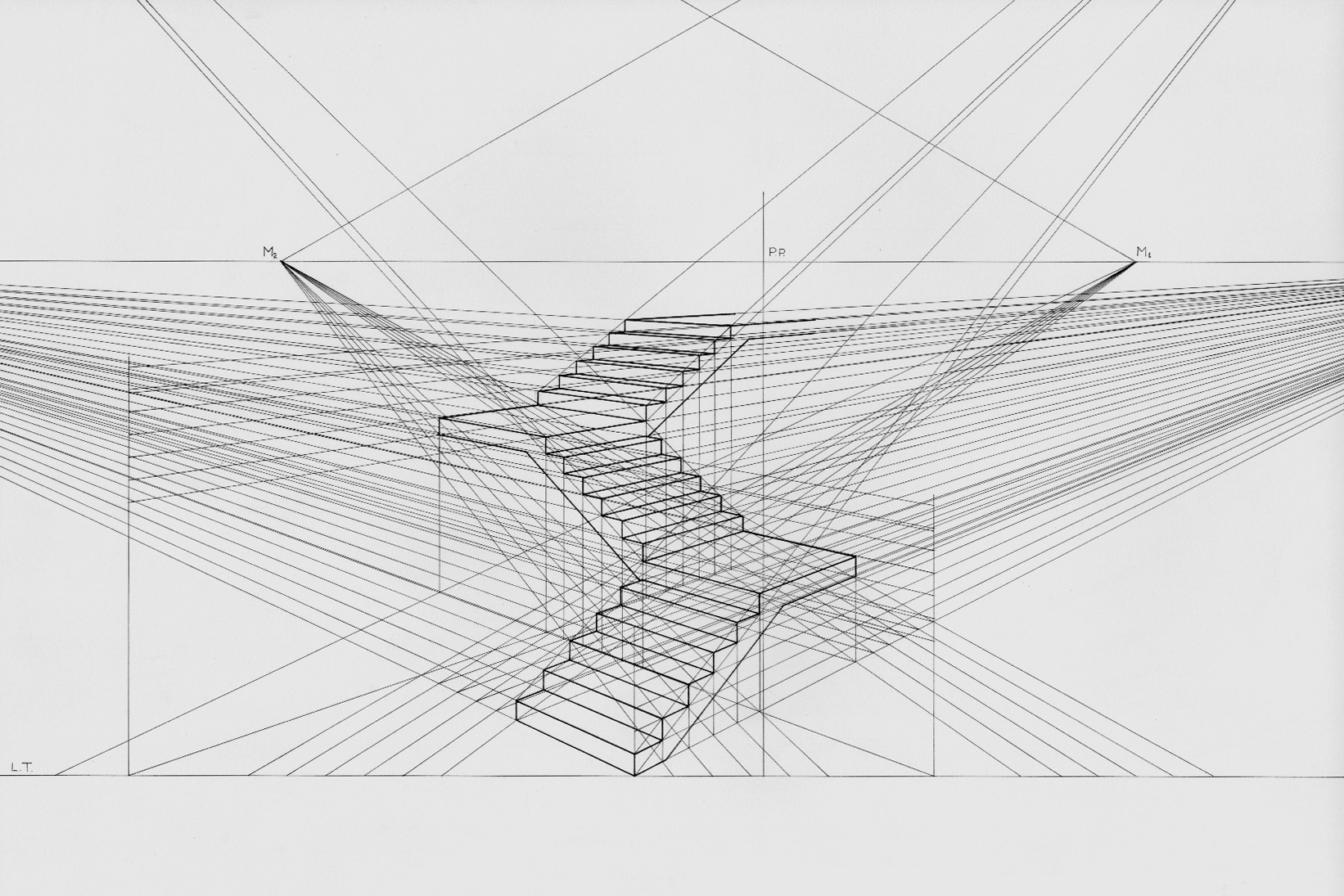

Control is a game about perspective—perspective as a mental view of the world (“from my perspective”), perspective as a matter of truth claims (“I’m trying to maintain my perspective”), and perspective as a technique of representing three-dimensional objects in space (perspective drawing, “the window is in perspective to the door”). After an opening sequence, the game begins with Jesse walking into the headquarters for the Federal Bureau of Control, a government agency that studies inexplicable paranormal events (think: The X-Files meets mid-century noir). “Fair warning,” Jesse narrates, “this is going to be weirder than usual. Can’t be helped. You called me, so here I am.” To whom is Jesse narrating? Is she speaking to the player? We learn the answer to these questions later in the game, but the effect of this intimacy is both to invite and to act against our identification with her as the protagonist of the story. Perspective is, then, an encounter with the limits of what we can know about others and about the world around us.

In a future newsletter, I’ll talk more about architecture and infrastructure in video games. For now, it’s enough to note the monstrous, brutalist design of the Oldest House (a haunted house/office building where the Federal Bureau of Control is located in midtown New York). Once associated with socially-progressive design, brutalist architecture has since earned a reputation as cold, depersonalized, ugly, and austere. Thematically, it’s an appropriate setting for the Federal Bureau of Control, which, like any government institution, is at once a place where the conspiratorial machinations of vertical hierarchy (“the Deep State”) meet the under-appreciated unity of horizontal sociality (I collected a number of in-game objects that mentioned a book club, for example). Brutalism also speaks to perspective as a matter of the arrangement of social space. When we look at a brutalist building, it often feels as though we were looking at a perspective drawing, with the lines of the building radiating toward the horizon. At the same time, when we say something is “in perspective,” we mean it is in proportion, and brutalist architecture represents both the absolute leveling of social relations (with its ethos of egalitarian design) and the disruption of received arrangements (with its large-scale forms and flat surfaces).

Throughout Control, we move in and out of different levels of the Oldest House, and the architecture of the building responds to our progress through the game. Saving entails taking control of various “access points” throughout the levels, and rooms will often reorganize and reshape in response to our actions. For one of the most memorable challenges in the game—The Ashtray Maze—you have to navigate through a labyrinthine set of hallways as they shift and change around you. It’s a stunning moment in the game (accompanied by some really kickass sound design), and one which really warps your sense of reality, proportion, and direction.

We might say that Control is both in and out of perspective. It is both familiar and intimate—the story of a sister’s search for her lost brother—and monstrously incomprehensible. There’s a Lovecraftian element to the game, and as you progress, you are steadily confronted by some mysterious, cosmic being known as the Hiss, which has infected members of the Bureau and reduced them to zombie-like automatons. The impression I get playing the game is that meaning-making, the process by which the game crafts narrative from the pure flow of gameplay, is a battle against that noise, like the slow search for a signal in the static of a radio dial.3 A point I’m going to return to again and again in this newsletter is that video games matter because they are functionally about how and why things matter. Video games represent “mattering” as a ratio of experience and narration, a function between “pointless fun” and the “seriousness” of art. In playing a game like Control we do not so much as choose one side or the other as we lobby between them in the process of bringing into perspective the meaning of the game.

Of course, by suggesting that meaning is “discovered,” I run the risk of sounding conspiratorial, and the game’s title hints at the ways we can manipulate someone simply by tweaking their perspective on the world. Midway through the game, Jesse learns that the Bureau has been surveilling her for years, watching and maybe even manipulating her from a distance. The Bureau, then, is something like an metaphor for the player—a manipulating presence that determines Jesse’s actions and behavior without her knowledge. But, a control is also a fixed standard, a way of checking the results of an experiment by controlling for external variables. Where does meaning reside: in the power or authority to determine or in the self-restraint to remain unchanged? I think one of the more interesting things about Control is that it flips these questions on their head. Who has power or authority? We don’t know. Who remains unchanged? Nobody. That these questions remain unanswerable is, perhaps, all the more reason to seek out their answer.

The thing about perspective is that it’s the point of identification around which a number of art forms rotate. Novels, for example, are often animated by the assumption that perspective is crucial for how we relate to characters. It’s also a bit of a cliché in contemporary literature to assume that perspective is ethical, insofar as how we relate to characters (whether by identification or appreciation or disgust or recognition) is a proxy for how we relate to people. But, when we play video games, we control a character’s actions and, therefore, control the frame by which their perspective is rendered for us. Unlike novels, which are fixed by the time we read them, video games are more flexible by design. Does that flexibility change our relationship to the character? Does being able to “control” the avatar on our screen shape how we identify with that character’s perspective, and, if so, how is that different from the way identification works in fiction or film? I’m not sure how to answer these questions right now, but Control does an amazing job animating them as concerns.

What I’m Playing

After I finish Control, I might try to play the remake of Final Fantasy 7. I’m not crazy about RPGs, but it comes highly recommended by my husband. I need a break from open-world games (“open-world fatigue”), so I think I’ll probably focus on smaller indie games in the coming months.

What I’m Reading

I just finished Haruki Murakami’s second novel, Pinball, 1973. I’m trying to read more books in translation this year as an excuse to read a lot of Murakami and to finish reading (finally) Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet. I liked Pinball more than Murakami’s first novel, Hear the Wind Sing. You get the sense reading the two novels in quick succession of a novelist who is not only learning his particular style but what the limits of that style are.

-

Linda Hutcheon, A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2013), 55. ↩

-

This overview mostly holds for 3D games. Things are a little more complicated in 2D games, which employ things like “top-down” perspective, side-scrolling perspective, and pseudo-three-dimensionality (isometric, oblique, parallax). ↩

-

Does this metaphor even track anymore?? ↩

Comments